The Many Faces of Grief — and Why We Must Grieve Together

I remember being told when I cried, “I’ll give you something to cry about.”

In that moment, tears were framed as weakness.

That message didn’t belong to one gender, or one generation.

It shaped all of us.

Girls learned that crying made them dramatic, emotional, or easily dismissed.

Boys learned that crying meant weakness, that vulnerability threatened belonging and strength.

Different messages.

Same outcome.

Both were taught to silence grief.

And when grief is not allowed to be felt, it doesn’t disappear.

It finds another way to live.

Grief has many faces.

It can turn inward as depression, numbness, anxiety, exhaustion—and illness.

The body begins to carry what the heart and voice were never allowed to express. What was never witnessed emotionally often asks to be witnessed physically.

It can turn outward as anger, rage, defensiveness, blame, or violence.

It can show up as control, resentment, withdrawal, or disconnection.

It can take the form of addiction—seeking relief from pain that was never held.

Grief can also live in patterns of victimization and abuse.

When pain is silenced for too long, power can replace connection.

Unexpressed grief can harden into domination, control, or harm.

And grief that was never protected can settle into victimhood—not as weakness, but as a nervous system shaped by survival.

This is not blame.

It is understanding.

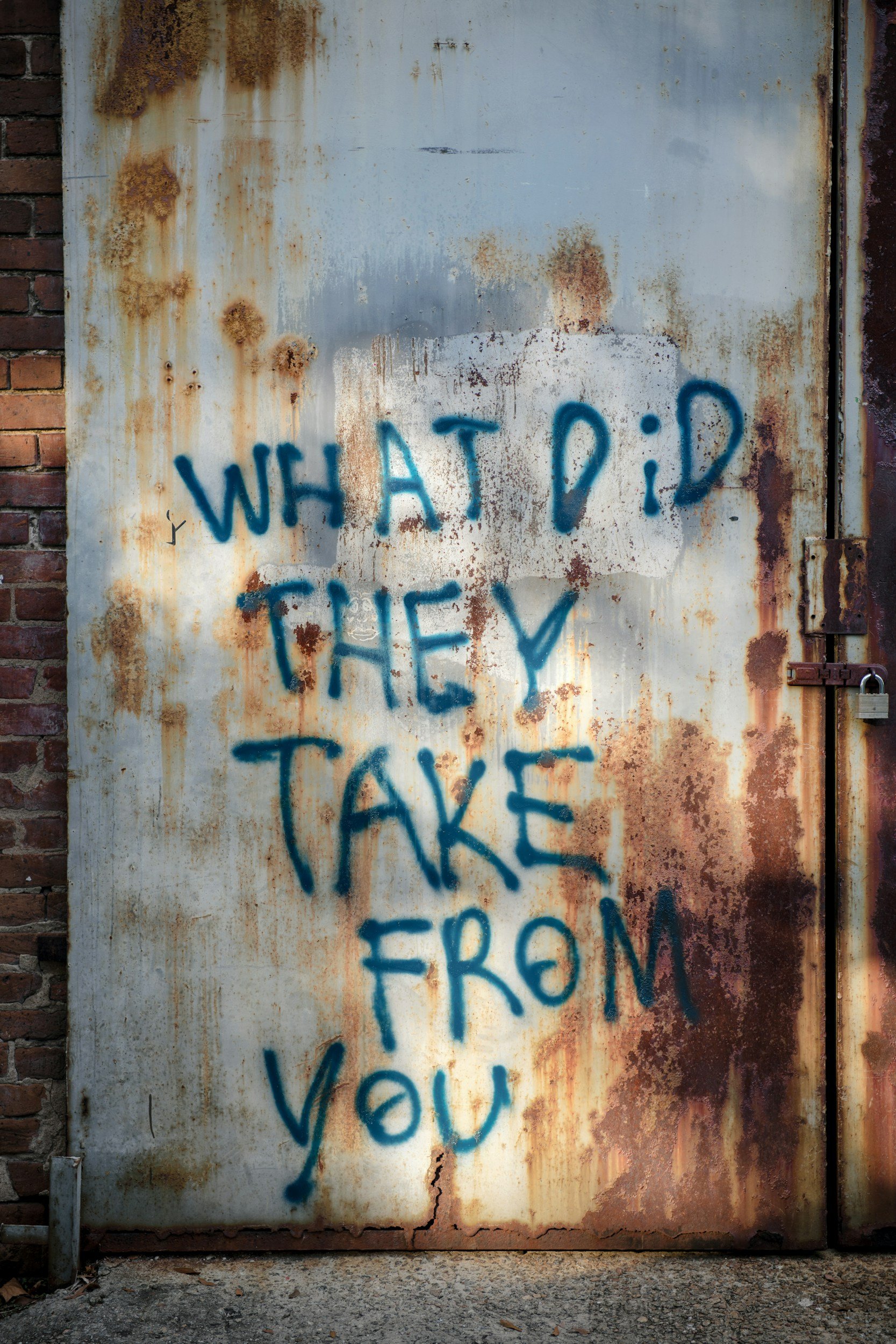

And yes—grief also shows up as political division.

When grief has no container, it looks for an enemy.

When loss is not named, it hardens into us versus them.

When people feel unseen, unheard, and unsafe, pain turns into polarization.

What we are living inside of today is not just disagreement.

It is ungrieved loss playing itself out publicly and privately.

Loss of safety.

Loss of trust.

Loss of belonging.

Loss of shared ground.

None of this is a failure of character.

It is grief without a home.

In the teachings of Sobonfu Somé, from the Dagara people tradition, grief was never meant to wait for crisis.

She said they grieved regularly, and they grieved together.

Grief was communal maintenance.

Soul hygiene.

A way of tending pain before it hardened into illness, addiction, conflict, abuse, or division.

When something hurt, it was brought to the circle.

When someone carried pain, they were not left alone with it.

Sobonfu taught that when grief is expressed, it does not need to disguise itself.

But when it is denied, it will emerge somewhere else—not because people are broken, but because grief is carrying too much by itself.

Grieving together was not weakness.

It was strength.

It was how the village stayed in right relationship—with one another, with the ancestors, and with life.

This is what our culture has forgotten.

We have privatized grief.

Medicalized it.

Politicized it.

And asked individuals to carry what was once held by community, ritual, and rhythm.

Grief was never meant to be carried alone.

It was meant to be witnessed.

When grief is shared, it softens.

When it is sounded, it moves.

When it is held in community, the body no longer has to carry it alone.

This spring, I will be holding a Community Grief Ritual inspired by the teachings and tradition of Sobonfu Somé at the Rowe Conference Center.

This is not therapy.

It is not fixing.

It is remembering.

Remembering that grief has many faces.

Remembering that tears are not weakness.

Remembering that healing begins when grief no longer has to live in silence—or in the body.

If something in you feels unspoken, unfinished, or quietly waiting—you are welcome.

Grief does not ask to be solved.

It asks to be witnessed.

And when we grieve regularly and together, we begin to heal—not just ourselves, but the culture we are living inside.